By Behnam Zoghi Roudsari, Central European University

On 2 November 2024, a women’s rights protest in Iran drew extensive attention from Western media. Frustrated with Iran’s restrictive dress code laws, a woman chose to strip down to her underwear in front of her university entrance. While media outlets focused on her act of resistance, two other significant achievements by Iranian women – within a governmental framework – during the same week went largely unnoticed. Without minimising protests, a holistic understanding of the women’s rights movement in Iran requires looking at other – policy-oriented – avenues of progress.

While the Iranian women’s movement often receives substantial attention in Western media, this attention is typically skewed toward visible acts of defiance, especially towards the dress code, which perpetuates a straightforward narrative. However, the Iranian women’s struggle is multi-dimensional and involves other, less-publicised, channels where some women, rather than seeking to challenge the government, attempt to bring more female voices to the table and pursue long-standing aspirations and incremental reforms, such as pushing for the adoption of the bill to protect women from violence and increasing political representation through female ministers. In the first week of November, two landmark achievements underscore such forms of progress.

One milestone was the appointment of Kowsar Yousefi, a former World Bank consultant, as Head of the Board of Supervisors at the Central Bank of Iran. Yousefi holds a PhD in economics from the University of Texas at Austin and completed postdoctoral research at Northwestern University. She is among the few graduates from Iran’s prestigious Sharif University who returned to the country after earning her Ph.D. from a U.S. university and has served as an Associate Professor at the Institute for Management and Planning Studies, as well as an Adjunct Professor at Sharif University. This appointment, firstly, marks an unprecedented move for a woman in Iran’s central banking leadership. But more interestingly, her recent research has focused on female labour force participation in Iran. This makes Yousefi stand out, as she possesses a clear understanding of the obstacles hindering female participation. This is especially significant given that some previous female appointments were criticized for lacking a mindset that supported women’s aspirations.

Another noteworthy achievement came from Shina Ansari, the recently appointed vice-president and head of Iran’s Environmental Protection Organization. Ansari is an expert on various environmental topics, ranging from climate change to air pollution to green construction to ozone layer protection. Before her appointment to this position, as an activist in civil society, she had campaigned against the use of Mazut – a low-quality fuel oil – in power plants, through articles on independent media platforms and public speeches, highlighting its consequences for the environment and health. On November 7th, Ansari ordered the cessation of Mazut as fuel in three major power plants in Karaj, Isfahan, and Arak, citing serious environmental concerns. This decision, which resulted in hours of power outages in some of the most populated Iranian cities, was particularly bold, as it risked significant public backlash. For example, in 2019, attempts at energy subsidy reform sparked nationwide protests, leaving policymakers hesitant to implement changes in the energy sector ever since. Despite the risks, Ansari’s decision, requiring significant advocacy, political negotiation, and coordination, represents one of the new administration’s boldest policy moves.

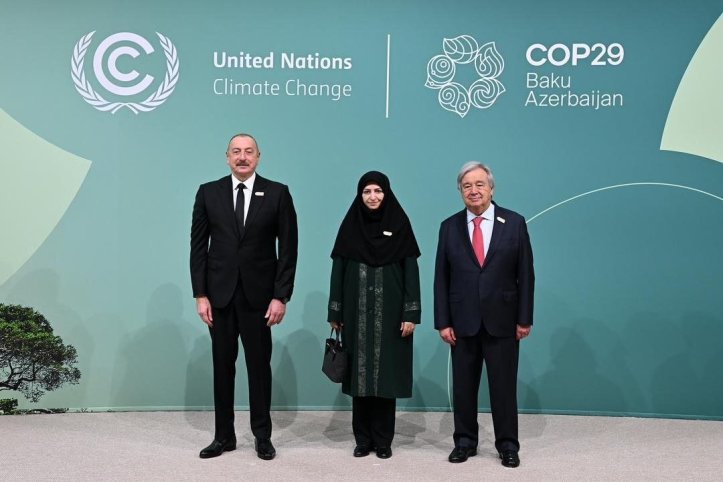

These appointments represent institutional responses by Iran’s governing system to the long-standing demands of the Iranian women’s movement. Iranian women’s rights activists have pursued a wide range of demands, including, but not limited to, ending domestic violence, upholding civil and human rights, supporting the establishment of women-led NGOs, promoting egalitarian values, and eliminating discriminatory laws and policies. Among these, the appointment of qualified, egalitarian cabinet—particularly women ministers in the cabinet—has consistently been one of the most widely agreed-upon demands. Though the women’s rights movement in Iran is mostly portrayed in media in the form of defiant protest, advocacy in Iran is not monolithic and there do exist channels of effective engagement between Iranian civil society and the Iranian hybrid political system. Kadivar and Abedini (2020) examine this issue, demonstrating how the momentum of social movements translates into formal political change in Iran. As an example of how these mechanisms work, this paper explains how activism around 2009 presidential elections shifted the presidential candidate Mir Hossein Musavi’s discourse from a focus on economy and management to an emphasis on women’s rights and freedom of speech. Furthermore, the newly elected Pezeshkian government, emerging from the reformist camp, has deep-rooted solidarity with the women’s movement and seeks to address the demands of its electoral base. Notably, during a critical electoral event leading to the presidency of Masoud Pezeshkian, Mohammad Reza Jalaeipour —an Iranian social activist, well-known for his recent activism for the women’s right movement— raised three key demands , one of which was the appointment of women to high-ranking political positions. In response to these demands, Mohammad Reza Aref, the First Vice President, in one of his first moves issued an important directive to all executive bodies and provincial offices, emphasizing the inclusion of women in managerial positions. Currently, 28 women are appointed to the mid-level management positions in the Pezeshkian administration. Pezeshkian’s cabinet includes five women – including the second female minister in the history of the Islamic Republic – compared to just two in the former administration. These developments signal a significant shift in trajectory which reflects a growing commitment to gender inclusion and representation in Iran’s political and administrative landscape.

These achievements by Ansari, Yousefi, and other Iranian women like Farzaneh Sadegh Malvajerd, Minister of Roads and Urban Development, Fatemeh Mohajerani, Spokesperson of the Government, and Zahra Behrouz Azar, vice president of Iran for women and family affairs, who have ascended to influential roles in government, deserve acknowledgment as they represent another current within the women’s rights movement. In a system beset by international sanctions, social instability, and constant geopolitical pressure, where those outside narrow political circles, which are dominated by men, seldom gain decision-making roles – even if they possess considerable expertise – the efforts of women like Ansari and Yousefi illustrate that while the path to progress is difficult, it does exist. Ignoring these more nuanced dynamics leads to an image of the Iranian political system that can be used to justify external intervention – such as sanctions and threats of war against Iran – that cripple rather than support Iranian civil society’s drive for change.